Third Great Awakening

Wikipedia reports that The Third Great Awakening refers to a hypothetical historical period proposed by William G. McLoughlin that was marked by religious activism in American history and spans the late 1850s to the early 20th century.[1] It affected pietistic Protestant denominations and had a strong element of social activism.[2] It gathered strength from the postmillennial belief that the Second Coming of Christ would occur after mankind had reformed the entire earth. It was affiliated with the Social Gospel Movement, which applied Christianity to social issues and gained its force from the Awakening, as did the worldwide missionary movement. New groupings emerged, such as the Holiness movement and Nazarene movements, and Christian Science.[3]

The era saw the adoption of a number of moral causes, such as the abolition of slavery and prohibition. However, some scholars, such as Kenneth Scott Latourette, dispute the thesis that the United States ever had a Third Great Awakening.[4]

Overview

This was a time that continued from The Second Great Awakening put more of a stress on the social gospel than on improving our relationship with Jesus Christ. Revivals occurred, especially during the Civil War, but there was no significant change in the importance of religion in governance or society as happened in the first two awakenings. Instead of society realizing the need to reform individuals through repentance, religion was often used to accomplish political social goals.

As a continued result from the Second Great Awakening, the American Protestant mainline churches grew rapidly in numbers, wealth and educational levels, leaving their frontier beginnings and becoming more established in towns and cities and more respectable in society. Writers and influential leaders in society such as Josiah Strong advocated a muscular Christianity with systematic outreach to the unchurched in America and around the globe. Colleges and universities were continuing to be built to train the next generation of religious leaders. Churches fully supported missionary societies, and held missionaries in high regard.[6] This new continued missionary activity brought the United States further from the reformation of Europe and its predestination.

In the north, Pietistic mainline Protestants used their influence to affect politics and they tended to support the Republican Party, urging them to support prohibition and other social reforms.[7][8] The American Civil War slowed down any supposed awakening activity in the north. But in the South,, the Civil War stimulated revivals, especially the Confederate States Army revival in General Robert E. Lee‘s army.[9]

After the war, Dwight L. Moody continued the efforts of efforts of The Second Great Awakening and made revivalism the centerpiece of his activities in Chicago by founding the Moody Bible Institute. Ira Sankey aided the efforts with his many hymns.[10]

Religions used their political clout across the nation, crusading in the name of religion for the prohibition of alcohol. The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union mobilized Protestant women for social crusades against liquor, pornography and prostitution. Mixing politics and religion they sought to affect even more change with a demand for woman suffrage.[11] The Gilded Age plutocracy came under sharp attack from the Social Gospel preachers and with reformers in the Progressive Era. Historian Robert Fogel identifies numerous reforms, especially the battles involving child labor, compulsory elementary education and the protection of women from exploitation in factories.[12]

Colleges associated with churches rapidly expanded in number, size and quality of curriculum. The promotion of “muscular Christianity” became popular among young men on campus and in urban YMCA‘s, as well as such denominational youth groups such as the Epworth League for Methodists and the Walther League for Lutherans.13

New religions

Mary Baker Eddy introduced Christian Science, which gained a national following.[14] In 1880, the Salvation Army denomination arrived in America. Although its theology was based on ideals expressed during the Second Great Awakening, its focus on poverty was of the Third. The Society for Ethical Culture was established in New York in 1876 by Felix Adler attracted a Reform Jewish clientele. Charles Taze Russell founded the Bible Students movement, which later split into the “Jehovah’s Witnesses” of today.

The Social Gospel was very strong in all area, Jane Addams‘s Hull House in Chicago established the settlement house movement and the vocation of social work with religious thought was established and worked for a better world today without demanding repentance or a relationship with Jesus Christ.[15]

The New Thought movement expanded as Unity and Church of Divine Science were founded. These all focused on the divine within each individual and that man is inherently good and not evil. This was the origin of today’s positive confession, health and wealth and healing gospels that are so prevalent.

The Holiness and Pentecostal movements

The goal of the Holiness movement in the Methodist Church was to move beyond the one-time conversion experience that the revivals produce, and reach entire sanctification.[16] The Pentecostals went one step further, seeking what they called a “baptism in the spirit” or “baptism of the Holy Ghost” that enabled those with this special gift to heal the sick, perform miracles, prophesy, and speak in tongues.[17] These new ideas were not found in the New or Old Testaments, but were added by people seeking more experiential ways of finding God. As these trends continued, the Bible was used less and influential people were trusted more. We see a mixture of truth and error that has continued to today. There was influence from this time, but it could not be considered a great awakening.

Bibliography

- Abell, Aaron. The Urban Impact on American Protestantism, 1865–1900 Harvard University Press, 1943.

- Ahlstrom, Sydney E. A Religious History of the American People. Yale University Press, 1972.

- Bordin, Ruth. Woman and Temperance: The Quest for Power and Liberty, 1873–1900 Temple University Press, 1981.

- Curtis, Susan. A Consuming Faith: The Social Gospel and Modern American Culture. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.

- Dieter, Melvin Easterday. The Holiness Revival of the Nineteenth Century Scarecrow Press, 1980.

- Dorsett, Lyle W. Billy Sunday and the Redemption of Urban America Eerdmans, 1991.

- Dorsett, Lyle W. A Passion for Souls: The Life of D. L. Moody. Moody Press, 1997.

- Edwards, Wendy J. Deichmann. and Carolyn De Swarte Gifford. Gender and the Social Gospel (2003) excerpt and text search

- Evensen; Bruce J. God’s Man for the Gilded Age: D.L. Moody and the Rise of Modern Mass Evangelism (2003) online edition

- Findlay, James F. Dwight L. Moody: American Evangelist, 1837–1899 University of Chicago Press, 1969.

- Finke, Roger, and Rodney Stark. The Churching of America, 1776–1990: Winners and Losers in Our Religious Economy Rutgers University Press, 1992.

- Fishwick, Marshall W. Great Awakenings: Popular Religion and Popular Culture (1995)

- Fogel, Robert William. The Fourth Great Awakening and the Future of Egalitarianism (2000)

- Hutchison William R. Errand to the World: American Protestant Thought and Foreign Missions. University of Chicago Press, 1987.

- Jensen, Richard. The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888–1896 (1971)

- Keller, Rosemary Skinner, Rosemary Radford Ruether, and Marie Cantlon, eds. Encyclopedia of Women And Religion in North America (3 vol 2006) excerpt and text search

- Long, Kathryn Teresa. The Revival of 1857–58: Interpreting an American Religious Awakening Oxford University Press, 1998 online edition

- Luker, Ralph E. The Social Gospel in Black and White American Racial Reform, 1885–1912. (1991)online edition

- Luker, Ralph E. “Liberal Theology and Social Conservatism: a Southern Tradition, 1840–1920.” Church History v 10#2 1981. pp 193–207 p online edition

- McClymond, Michael, ed. Encyclopedia of Religious Revivals in America. (2007). Vol. 1, A–Z: xxxii, 515 pp. Vol. 2, Primary Documents: xx, 663 pp. ISBN 0-313-32828-5/set.)

- McLoughlin, William G. Modern Revivalism: Charles Grandison Finney to Billy Graham 1959.

- McLoughlin, William G. ed. The American Evangelicals, 1800–1900: An Anthology 1976.

- Marty, Martin E. Modern American Religion, Vol. 1: The Irony of It All, 1893–1919 (1986); Modern American Religion. Vol. 2: The Noise of Conflict, 1919–1941 (1991)

- Marsden, George M. Fundamentalism and American Culture: The Shaping of Twentieth-Century Evangelicalism, 1870–1925 (1980). very important history online edition

- Miller, Randall M., Harry S. Stout, and Charles Reagan. Religion and the American Civil War (1998) excerpt and text search; complete edition online

- Shenk, Wilbert R., ed. North American Foreign Missions, 1810–1914: Theology, Theory, and Policy (2004) 349pp important essays by scholars excerpt and text search

- Sizer, Sandra. Gospel Hymns and Social Religion: The Rhetoric of Nineteenth-Century Revivalism. Temple University Press, 1978.

- Smith, Timothy L. Called Unto Holiness, the Story of the Nazarenes: The Formative Years. Kansas City: Nazarene Publishing House, 1962.

- Smith, Timothy L. Revivalism and Social Reform: American Protestantism on the Eve of the Civil War Johns Hopkins Press, 1980.

- Ward, W. R. The Protestant Evangelical Awakening Cambridge University Press, 1992.

- Weisberger, Bernard A. They Gathered at the River: The Story of the Great Revivalists and Their Impact upon Religion in America 1958.

Primary sources

- Carroll, H. K. The Religious Forces of the United States, Enumerated, Classified and Described: Returns for 1900 and 1910 Compared with the Government Census of 1890: Condition and Characteristics of Christianity in the United States (1912), very useful summaries of each denomination and detailed statistics. complete text online free

- McLoughlin, William G. ed. The American Evangelicals, 1800–1900: An Anthology 1976.

Notes

1. William G. McLoughlin, Revivals Awakenings and Reform (1980)

3. · Robert William Fogel, The Fourth Great Awakening and the Future of Egalitarianism (2000)

5. · Sydney E. Ahlstrom, A Religious History of the American People (1972) pp 731-872

6. · Paul Kleppner, The Third Electoral System, 1853–1892: Parties, Voters, and Political Cultures (2009)

7. · Jensen (171)

8. · Randall M. Miller, et al, eds. Religion and the American Civil War 1998

9. · James F. Findlay Dwight L. Moody: American Evangelist, 1837–1899 (2007

10. · Ruth Bordin, Women and Temperance: The Quest for Power and Liberty, 1873–1900 (1981)

11. · Fogel p 108

12. · Paul A. Varg, “Motives in Protestant Missions, 1890–1917,” Church History 1954 23(1): 68–82

13. · David P. Setran, “Following the Broad-Shouldered Jesus: The College YMCA and the Culture of Muscular Christianity in American Campus Life, 1890–1914,” American Educational History Journal 2005 32(1): 59–66,

14. · Stephen Gottschalk, Emergence of Christian Science in American Religious Life (1979)

15. · Louise W. Knight, Jane Addams: Spirit in Action (2010)

16. · Charles Edwin Jones, Perfectionist Persuasion: The Holiness Movement and American Methodism, 1867-1936 (1974)

17. · Augustus Cerillo, Jr., “The Beginnings of American Pentecostalism: A Historiographical Overview,” in Pentecostal Currents in American Protestantism, ed. by Edith L. Blumhofer, Russell P. Spittler, and Grant A. Wacker (1999).

Fourth Great Awakening

THE FOURTH GREAT AWAKENING

Wikipedia reports The Fourth Great Awakening was a Christian religious awakening that some scholars — most notably economic historian Robert Fogel — say took place in the United States in the late 1960s and early 1970s, while others look at the era following World War II. The terminology is controversial, with many historians believing the religious changes that took place in the US during these years were not equivalent to those of the first three great awakenings. Thus, the idea of a Fourth Great Awakening itself has not been generally accepted. (As has not the Third Great Awakening!!) [1]

Whether or not they constitute an awakening, many changes did take place. The “mainline” Protestant churches (Seven Sisters of American Protestantism: United Methodist Church, Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (not Confessional Lutheran), Presbyterian Church USA, Episcopal Church, American Baptist Churches (Congregationalists, tracing its history to the First Baptist Church in America of 1638 and the Baptist congregational associations which organized the Triennial Convention in 1838), United Church of Christ and Disciples of Christ. Additionally, Quakers, Reformed Church in America and African Methodist Episcopal) weakened sharply in both membership and influence while the most conservative religious denominations (such as the Southern Baptists and Missouri Synod Lutherans) grew rapidly in numbers, spreading across the United States. They had grave internal theological battles and schisms, but also became politically powerful. Other evangelical and fundamentalist denominations also expanded rapidly. At the same time, secularism grew dramatically, and the more conservative churches saw themselves battling secularism in terms of issues such as gay rights, abortion, and creationism.[2][3]

Missouri Synod Lutherans are a confessional Lutheran denomination, which designates those who accept the doctrines taught in the Book of Concord of 1580 in their entirety because they are considered to be completely faithful to the teachings of the Bible. Book of Concord or Concordia, is the historical doctrinal standard of the Lutheran Church, consisting of ten credal documents recognized as authoritative in Lutheranism since 1580. While they share many beliefs with fundamental Christianity, there are also glaring differences, not the least of which would be that a central organization controls the individual churches.

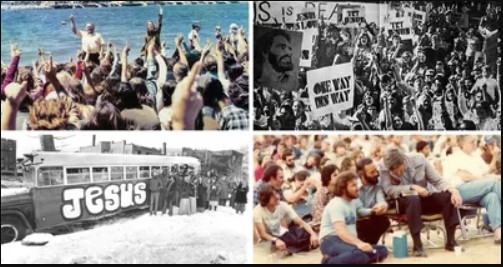

Concomitant (a phenomenon that naturally accompanies or follows something) to the power shift was a change in evangelicalism itself, with new groups arising and existing ones switching their focus. Seeing the error of the social gospel, there was a new emphasis on a personal relationship with Jesus from newly styled ‘non-denominational’ churches and ‘community faith centers’. This is definitely a good outgrowth. This period also saw the rise of non-traditional churches and megachurches (2,000 or more attendees in average weekend) with conservative theologies and a growth in parachurch organizations (Christian faith-based organizations that usually carry out their mission independent of church oversight. Many are good and provide necessary support to Christians. Medi-Share health sharing is one example) while mainline Protestantism lost many members. The Jesus Movement is considered by some to be part of the Fourth Great Awakening.

Vinson Synan (1997) argues that a Charismatic Movement occurred between 1961 and 1982, followed by the Jesus Movement from late 1960’s to late 1980’s. The Charismatic Movement stemmed from a Pentecostal movement from the Azusa Street revival from Los Angeles that placed emphasis on experiencing what they saw as the gifts of the spirit, including speaking in tongues, healing, and prophecy. It also focused on strengthening spiritual convictions through these gifts and through signs taken to be from the Holy Spirit. Originally a Protestant movement, its influence spread to some in the Roman Catholic Church at a time when Catholic leaders were opening up to more ecumenical beliefs, to a reduced emphasis on institutional structures and an increased emphasis on lay spirituality. The Jesus Movement was very similar, just with a west coast flavor. Each left the traditional beliefs of fundamental Christianity with its new emphasis on experiential Christianity apart from the Bible. A new type of social gospel crept in with more “tolerance” of sinful ideas.

Trends

Organized religion has changed in the face of secularizing pressures after World War II. Notable examples include the proliferation of mega-churches, the growth of denominations such as the Assemblies of God and the Southern Baptists, as well as offshoot groups such as the Latter-day Saints (Mormons), and the post-World War II influence of three world-historical religious leaders: Martin Luther King Jr., Billy Graham, and Pope John Paul II. Mega-churches won attention for the simple reason that 10 churches with 2,000 members were more visible than 100 churches with 200 members. The populist denominations’ growth coincided with the simultaneous decline of the mainline bodies. While the former trend did not come at the expense of the latter (it represented different fertility and retention rates, not switching), to the media and many ordinary observers those developments signaled the aggressive swelling of religious political strength. Finally, it would be hard to find any other period of U.S. history that witnessed three leaders who captured the hearts and minds of millions of Americans as King, Graham, and John Paul did. Unfortunately, conservative religions became a wing of the Republican Party, leaving their first love for politics. The liberal religions became a wing of the Democratic Party. Both left the idea of changing hearts to the way of improving society by obtaining votes.

The “mainstream” Protestant churches contracted sharply in terms of membership and influence as conservative churches grew in strength.

After World War Two, some conservative Christian denominations (including the Southern Baptists, Missouri Synod Lutherans, the Church of God, Pentecostals, Holiness groups and Nazarenes) grew rapidly in numbers and also spread nationwide. Some of these denominations, such as the Southern Baptists and Missouri Synod Lutherans, would go on to face theological battles and schisms from the 1960s onward. Many of the more conservative churches would go on to become politically powerful as part of the “religious right.” At the same time, the influence of secularism (the belief that government and law should not be based on religion) grew dramatically, and the more conservative churches saw themselves battling secularism in terms of issues such as gay rights, abortion, and creationism.[5] Liberal churches tended to band with secularism with such organizations as “Americans United For The Separation of Church and State” worked hard to champion secular rights with Barry Lynn as its founder. Barry Lynn is a liberal pastor, an ordained minister of the United Church of Christ.

Byrnes and Segers note regarding the abortion issue, “While more theologically conservative Protestant denominations, such as the Missouri-Synod Lutherans and the Southern Baptist Convention, expressed disapproval of Roe, they became politically active only in the mid and late 1970s.”[6][7] However, the political involvement of churches ranged from actively participating in organizations such as the Moral Majority and the Christian Coalition to adopting the much more indirect and unorganized approach of Missouri Synod Lutherans.[8] With these, religious differences were overlooked with the idea that the end justifies the means and Biblical truths can be compromised if the ends are justified.

· Balmer, Randall. Religion in Twentieth Century America (2001)

· Balmer, Randall, and Mark Silk, eds. Religion and Public Life in the Middle Atlantic Region: Fount of Diversity. (Lanham: AltaMira, 2006. 184 pp. ISBN 978-0-7591-0637-6.)

· Barlow, Philip, and Mark Silk, eds. Religion and Public Life in the Midwest: America’s Common Denominator? (Lanham: AltaMira, 2004. 208 pp. ISBN 978-0-7591-0631-4.)

· Bednarowski, Mary Farrell. New Religions and the Theological Imagination in America. Indiana U. Press, 1989. 175 pp.’ looks at Scientology, Unification Church, and New Age religion

· Blumhofer, Edith L., and Randall Balmer. Modern Christian Revivals (1993)

· Gallagher, Eugene V., and W. Michael Ashcraft, eds., Introduction to New and Alternative Religions in America Vol. 1: History and Controversies, xvi, 333 pp. Vol. 2: Jewish and Christian Traditions, xvi, 255 pp. Vol. 3: Metaphysical, New Age, and Neopagan Movements, xvi, 279 pp. Vol. 4: Asian Traditions, xvi, 243 pp. Vol. 5: African Diaspora Traditions and Other American Innovations, xvi, 307 pp. (Greenwood, 2006. ISBN 0-275-98712-4/set.)

· Houck, Davis W., and David E. Dixon, eds. Rhetoric, Religion, and the Civil Rights Movement, 1954–1965. (Baylor University Press, 2006. xvi, 1002 pp. ISBN 978-1-932792-54-6.)

· Keller, Rosemary Skinner, Rosemary Radford Ruether, and Marie Cantlon, eds. Encyclopedia of Women And Religion in North America (3 vol 2006) excerpt and text search

· McClymond, Michael, ed. Encyclopedia of Religious Revivals in America. (Greenwood, 2007. Vol. 1, A–Z: xxxii, 515 pp. Vol. 2, Primary Documents: xx, 663 pp. ISBN 0-313-32828-5/set.)

· McLoughlin, William G. Revivals, Awakenings, and Reform: An Essay on Religion and Social Change in America, 1607-1977 1978.

· Killen, Patricia O’Connell, and Mark Silk, eds. Religion and Public Life in the Pacific Northwest: The None Zone (Lanham: AltaMira, 2004. 192 pp. ISBN 978-0-7591-0625-3.)

· Lindsay, D. Michael. Faith in the Halls of Power: How Evangelicals Joined the American Elite (2007)

· Lindsey, William, and Mark Silk, eds. Religion and Public Life in the Southern Crossroads: Showdown States. (Lanham: AltaMira, 2004. 160 pp. ISBN 978-0-7591-0633-8.)

· Roof, Wade Clark, and Mark Silk, eds. Religion and Public Life in the Pacific Region: Fluid Identities. (Lanham: AltaMira, 2005. 192 pp. ISBN 978-0-7591-0639-0.)

· Shipps, Jan, and Mark Silk, eds. Religion and Public Life in the Mountain West: Sacred Landscapes in Transition. (Lanham: AltaMira, 2004. 160 pp. ISBN 978-0-7591-0627-7.)

· Synan, Vinson. The Holiness-Pentecostal Tradition: Charismatic Movements in the Twentieth Century. (2nd ed. 1997). 340 pp.

· Walsh, Andrew, and Mark Silk, eds. Religion and Public Life in New England: Steady Habits Changing Slowly. (Lanham: AltaMira, 2004. 160 pp. ISBN 978-0-7591-0629-1.)

· Wilson, Charles Reagan, and Mark Silk, eds. Religion and Public Life in the South: In the Evangelical Mode. (Lanham: AltaMira, 2005. 232 pp. ISBN 978-0-7591-0635-2.)

1. Robert William Fogel (2000), The Fourth Great Awakening & the Future of Egalitarianism; see the review by Randall Balmer, Journal of Interdisciplinary History 2002 33(2): 322-325

2. William G. McLoughlin (1978), Revivals, Awakenings and Reform: An Essay on Religion and Social Change in America, 1607-1977

3. Randall Balmer (2001), Religion in Twentieth Century America

4. Edith L Blumhofer and Randall Balmer (1993), Modern Christian Revivals

5. McLoughlin 1978, Balmer 2001

6. Timothy A. Byrnes, Mary C. Segers, eds. The Catholic Church and the politics of abortion (1992) p 158

7. Mark A. Noll, Religion and American politics: from the colonial period to the 1980s (1990) p 327

8. Jeffrey S. Walz and Stephen R. Montreal, Lutheran Pastors and Politics: Issues in the Public Square (Concordia, 2007)